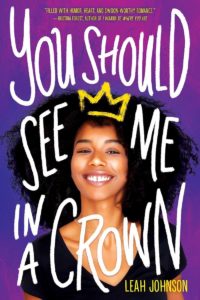

It’s Memorial Day when I talk to author (and “foremost Mighty Ducks personal essayist of our time”) Leah Johnson on the phone. Although, it feels more like any other day than a “holiday.” In fact, maybe describing it as, “any other day” feels too generous given the overall ongoing list of circumstances that pile on to how our days are moving and the ways in which they make us exhausted. At the time of our convo, it’s a week from the release of Leah’s debut novel You Should See Me in a Crown and like many authors at the moment, the experience has taken a detour. But as the protagonist, Liz Lighty reflects in the book, “We succeed in spite of, or maybe even because of, the odds against us.” And it seems that the multiple rules of the Lighty way prove to be the Leah way too.

I’ll start in what’s actually the midpoint of our conversation when we discuss her “‘The Mighty Ducks‘ Movies Taught Me How to Survive a Pandemic’ essay for Catapult. Raised in Indiana and a self-declared “eternal Midwesterner currently moonlighting as a New Yorker,” she wrote about returning home for quarantine, her anxieties around looking after her family and ensuring their health as best she can, and the ways in which our never-ending news cycle and ability to nonstop consume information can be overwhelming but feel required. She also writes about the ways in which The Mighty Ducks offers comfort in these circumstances. It’s an essay she’s proud of even as she describes the experience as “anxious making” and difficult for the honest way she wrote about mom.

“I know that my debut experience would have been wildly different–obviously, even without a pandemic–if I had been living here doing this. Like, even in the best of circumstances, it would have been wildly different from the way it would have been had I been in New York touring and doing events and stuff,” Leah admits. While her physical book tour has been canceled, she does have virtual book events she’s attending. Still, the experience of returning home to Indiana where You Should See Me in a Crown also takes place does have an effect. “It’s plunged me back into this strange sort of nostalgia and it’s caused me to really dig into a lot of the things that I was writing away from in my work.”

Being back in her childhood bedroom as an adult and as a writer, she reflects on her bookshelf and the realization that one of the books she read as a teen carried anti-Blackness that she didn’t catch before. “But when I was a kid, I had probably already internalized some of these ideas of like shame and Black Culture that I didn’t even notice what I was being indoctrinated with. And part of that indoctrination happens right in those books. And so, I’m like back here in this space, and I’m still unraveling so many of these ideas. Like, I’m constantly working to make sure that my writing doesn’t reflect any of that–like it reflects those sorts of anxieties I suppose, but doesn’t allow them to exist without critique,” she explains.

Leah shares how this experience has led to her confronting this realization of the influence (and potential harm) of the books she read when she was younger for the first time since leaving home and how it’s both been strange and affirming to confront it in this way when her book launch wasn’t intended to go this way. “Now, I’ve been here for all of those things (receiving finishing copies, the publication date, handing in the first draft of the second novel…) so I’ve been able to be surrounded by the people who I do this for which has been really grounding for me.”

She continues further explaining how returning to Indianapolis has led to grounding herself in her intentions. “I didn’t set out to become a writer because I wanted to get flown out across the country for a tour, I set out to become a writer because I wanted to get the stories in the hands of the teenagers who need them the most. So that is going to happen whether I’m touring, whether I’m going to big festivals, whether I’m sitting on panels with my literary heroes. The book is the book, the work is the work. So, I had to free myself from all those other expectations of what this tour was going to be and get back to the heart of it which is that, like, Leah you became a writer, so write,” she declares.

Writing has been a defining part of Leah’s life since she was really young, taking “varying degrees of passion” throughout. “By the time I reached high school, I knew that I wanted to be a reporter. My goal, I think freshman year like in my freshman yearbook, I was like, ‘I’m gonna be a political correspondent for the New York Times.’ That was my dream,” she says while also saying that fiction was her first passion as a kid. She gives credit to the ways in which being a reporter felt more attainable careerwise than being an author at the time as well. “I think, my love of storytelling just sort of evolved into something that I thought was possible and so I joined the newspaper really early on in high school, by the time I graduated, I was editor in chief and then I went on to college to essentially do the same thing.”

With the plan to be a political reporter, she worked for NPR affiliates and did work in beat reporting before venturing into long-form narrative writing. Her return to fiction writing became essential–for her and for her writing. “I was doing a lot of writing and reporting on issues of race and part of that–a large part of that–is because I went to a PWI and so it was a 4% Black population at my school and that means the population side of the J-School is even slimmer. So, if you looked around in the newsroom, there’s not a lot of Black folks down there to do the work, but the stories still need to get told. So, I found myself doing a lot of writing about stuff that was just like physically hurtful to write about.” She admitted to being able to feel it in her body when reporting on something painful. “Even though you’re supposed to keep this [objective] distance, I think, when you’re reporting but it’s impossible to have objective distance when I’m writing about dehumanization and erasure. Like, I’m talking about the fact that there are systems in place that want to eliminate me and the people I love from this planet.”

It was a thing she was/is capable of doing, but that doesn’t take away from the fact that the expectation was taxing and traumatic. “The more attention I got from my writing and the more praise I got for my writing, the deeper and deeper I felt that I had been entrenched in it,” she admits to feeling stuck. “It got to the point where it was physically draining for me to do that work and it felt like there was nobody looking and being like, ‘Hey Leah, how’s your heart?’ You know? It was like, ‘Hey Leah, you got nominated for a Columbia Scholastic Association Award!'” For the record, Leah immediately notes that’s not a humblebrag, but rather a call out to an often unacknowledged issue. “When I thought about it, I was only useful to people so far as I was mining my trauma for my work that could win this paper award–this work that nobody else on the paper was being able to do. So, in my first semester of my senior year, I think I was just worn down and so exhausted and it felt like nobody was really seeing me for me, you know? What it was I could actually bring to the table. I felt like I had painted myself into this corner and I was just like, ‘How do I recapture the fun? How did I recapture this love that I once had for this thing at one point?'” Which brought her back to revisiting fiction. On top of the anxieties of life post-graduation from undergrad and the initial internship she had set up, Leah decided to get her MFA in fiction writing at Sarah Lawrence.

That’s the work that I wanna do: the unraveling of what it means to be young and Black in America. How can we pinpoint joy instead of leaning into trauma? Or [how can we] write joy alongside trauma because that’s really the heart of this is that we are not people who are separate from pain because we inherited that.

Which (indirectly) brings us to the joy that is You Should See Me in a Crown. The coming-of-age novel centers on high school senior Liz Lightly who lives in the small, rich, prom-obsessed Campbell, Indiana despite existing as the exact opposite of all it is. As a (partially) closeted, Black girl with anxiety living with her grandparents and still coping with grief from the loss of her mom as her family struggles to make ends meet, she’s mastered the ways of being a wallflower as a means of survival. But, when her plans to attend the elite Pennington College and play in their world-famous orchestra while studying to become a doctor falls in jeopardy because her financial aid falls through, she decides to run for prom queen in the hopes of attaining the scholarship her school gives to the winners. Along with all of the requirements Liz has to do to stay in the running, she also has to face friendship troubles, the ways in which she prioritizes her loved ones over herself, and her relationship with the new girl Mack.

Which (indirectly) brings us to the joy that is You Should See Me in a Crown. The coming-of-age novel centers on high school senior Liz Lightly who lives in the small, rich, prom-obsessed Campbell, Indiana despite existing as the exact opposite of all it is. As a (partially) closeted, Black girl with anxiety living with her grandparents and still coping with grief from the loss of her mom as her family struggles to make ends meet, she’s mastered the ways of being a wallflower as a means of survival. But, when her plans to attend the elite Pennington College and play in their world-famous orchestra while studying to become a doctor falls in jeopardy because her financial aid falls through, she decides to run for prom queen in the hopes of attaining the scholarship her school gives to the winners. Along with all of the requirements Liz has to do to stay in the running, she also has to face friendship troubles, the ways in which she prioritizes her loved ones over herself, and her relationship with the new girl Mack.

As much as the story is grounded and acknowledges the ways that Liz has and is facing hardship, it’s also joyful and written for Liz Lighty to exist with the hope that Black, queer youth get to read a story about and for them. Still, Leah shares that she’s been thinking about the ways in which white people still need to work on learning how to engage with Black people’s work without talking about trauma. “I’m not interested really in putting my humanity on display so that you guys can realize why you should respect or why you should care more or whatever the case may be,” she says while explaining that even though the story deals with issues like race, class, and homophobia, the conversation needs to be about more than only demanding Black artists center or discuss their trauma for the sake of those asking to get woke points. “The burden of that should not be on Black artists, and yet, it is.”

I tell her that while reading the book, I immediately wanted to discuss writing joy with her to which she expresses excitement (and what also feels like relief) at the acknowledgment. “When you’re talking about Black literature, when you’re talking about queer literature, when you’re talking about Black, queer literature, then to write joy is to write something radical, you know what I’m saying? We exist in a world that aims to police our bodies, destroy our bodies in a lot of ways, so if I choose to pivot away from pain, if I choose to write into a reality in which a queer, Black girl gets a happy ending, then what I have done is inherently revolutionary. Like there’s something revolutionary in that.” There’s been many discussions on the use of joy in literature–notably the ways in which happy endings and joy are considered to be taking the easy way out in storytelling or questioned as “real writing.” But, as something that’s seen as such a general discussion, it’s pretty white and exclusionary. “Any conversation about Black joy can’t be looked at in the same lens as you would look at one of those white girl beach house love triangle novels from the early 2000s. Like that’s a different conversation entirely. Like, perhaps that is a cop-out but for us, we haven’t been granted the space and the opportunity to tell those stories for long enough for any of this to be overdone–for any of it to be even trope-y,” she says.

She gives credit to another writer of Black joy in YA, Kristina Forest for early on in the writing process helping calm her worries while writing and worrying about her use of YA tropes. “She was like, ‘Leah, we don’t have to worry about that the same way that white people should be worried about it because we haven’t had enough time to do that for our work to be overdone or for the market to be oversaturated with road trip books or prom books or stronger beach house novels. All of this is new territory for us.’ And so, I think about that every time I choose to craft a scene [away from] something terrible happening [and] instead of somebody like getting irreparably harmed in some way, which there’s space for those books as well. I think books like The Hate U Give and Dear Martin are these incredible contemporary YA texts that have changed the genre forever and I think alongside those novels, we have to have space for novels where Black kids just get to be Black kids,” she says.

“That’s the work that I wanna do: the unraveling of what it means to be young and Black in America. How can we pinpoint joy instead of leaning into trauma? Or [how can we] write joy alongside trauma because that’s really the heart of this is that we are not people who are separate from pain because we inherited that,” Leah continues. “I believe really deeply in ancestral trauma and I believe that we have to unravel that over the course of our lives. So, I’m never not going to be a product of intergenerational trauma. I’m never not going to be in the lineage of folks who were enslaved in this country. Like those things are in my bones. But, that doesn’t mean that I don’t also have space to fall in love or win prom queen or–or in my case win class clown–or you know, any number of different joyous experiences that white kids have always gotten to see stories about.”

When I tell her how Liz is a character I wish I had to read when I was a teen, she’s appreciative that her intention got across. “That’s like the first thing I think about most often,” she says. She gives credit to Elizabeth Acevedo next on her ongoing appreciation and uplifting of other Black YA writers. (It feels important to note that we both acknowledge her as amazing and as a quick aside, Leah golden-heartedly says she knows she’s mentioned Elizabeth a lot in interviews but she to be involved in every interview of hers “because her presence is so big.”) “She said this thing one time at Well-Read Black Girl Festival and I’ll never forget it. She said, ‘How can I write Black girls on the page so that when Black girls in the world come to it, they know that I love them? Like, how can I write these girls with so much care that they know that I see them and if nobody else gets them, nobody else loves them, nobody else cares for them, they’ll know that I care for them because of the way I crafted this character?’ So, I try to carry that into everything that I write: how can I write this girl so that a 16, 15-year-old Black girl who comes to this book knows that I see her and I love her? That’s what Liz is born out of,” she declares.

She notes that in that sense, she also understands people’s interest in asking her identity questions because of the ways in which the love and care she put into Liz mimics that of her lived experience. Aside from growing up in similar environments, she dealt with (undiagnosed) anxiety in high school, “In that way, Liz’s character came together because this was the first book I ever wrote and so I went straight to what I knew when I was crafting her and to move her through this world, I knew that we had to have somebody who loved her people fiercely but who also was deeply afraid of herself in a lot of ways and all of those things came together in the plot. Not seamlessly, we ran through a lot of drafts, but luckily, I had a really great editor who helped me cultivate that and hone in on exactly what it was I was trying to say and eliminate a lot of the noise that I think exist in the first draft of the novel.”

It’s said to be the dream of a lot of midwesterners to eventually make it out of their hometowns. In general, when someone is made to be smaller in a space, it makes sense why they’d wish for an out from the cramped space. Which is such an integral part of Liz’s journey, “I think that by the end of the book, Liz has a much stronger grasp on who she is and what she wants and I think at the beginning of the story, Liz wants to get out because she feels like there’s never going to be a place for her in her hometown.” Leah cites the epigraph of the book, a James Baldwin quote that reads, “The place in which I’ll fit will not exist until I make it.” “I think that by the end of the book, Liz has cultivated a space in her hometown where she doesn’t feel so alien anymore,” she says listing off some of the ways. (For the sake of *maybe* spoilers, I’ve redacted them, but Leah does say, “if you come to a Leah Johnson book, I guarantee you the two characters are gonna get together at the end.” To which I respond, “It’s what they deserve!” And then she follows up with, “It’s what they deserve! It’s what the Black kids deserve! Give them the happy endings!”)

I just think that we have to collectively work towards queer narratives where the reward for pain is not love. Like you don’t have to suffer in order to deserve love. You deserve love just because you’re a human being.

But, it’s that space and community that Leah says Liz was initially chasing after in her dreams of making it out. In terms of college though and what’s left for Liz to find, Leah hopes that similar to her college experience, she’d be able to get access to the kind of experiences and information that she couldn’t get before. For Leah, it was through taking classes in African American/African Diaspora studies and political engagement. “My vision for Liz and what I think Liz knows is that sometimes the only way that you can tap into all the things that you missed is to leave the place that raised you and I want that for her,” she says hoping that Liz would be able to grow and open up outside of her hometown.

Liz isn’t the only character that has to grow throughout the book though. Another is the character Jordan, who is one of Liz’s childhood best friends. Their start of freshman year also sees a change in their relationship with Jordan choosing to assimilate with his white classmates at the expense of Liz–which leads them going their separate ways throughout the rest of high school until they both end up running for court. Leah describes Jordan as being “trapped between those two worlds” in terms of being biracial and because of this, he needs those four years apart. “I think Jordan needed that time to grow to that type of person who could be a decent person to Liz. I don’t know if they could’ve been friends freshman year because he needed some work, honey,” she says. “Jordan had to do some serious heart work and I think even if he was apologetic at that moment, I don’t know if he was ready to do what needed to be done to protect Liz and advocate for her and essentially maybe alienate his teammates to protect this girl, I don’t think he was able to do that back then. Which honestly, when we’re 15, all of us are making really stupid choices.”

Jordan’s arc in the book is a focus on that heart work and how he can make things right with Liz which he makes a strong effort to do. “Also, here’s the thing about Liz, Liz forgives people really easily,” she says also addressing outside responses. “Liz is a forgiving person, she’s the type of person who would rather hold her friends close than push them away from her.” She cites Liz’s relationships with Gabi and Mack in that regard as well. “But, I know she would have been too eager to forgive Jordan and I don’t think that she would have been able to grow as a person had they’d been able to stay friends that whole time,” she admits.

When it comes to Liz, such a defining part of the way she goes through life is in her empathy and how that channels itself into her doing all she can for those she loves while also always trying to have an understanding for others. When I bring this up, Leah confirms that it was intentional that Liz’s goals would point outward. “Liz doesn’t want to become a doctor because she feels passionate about medicine. Liz wants to become a doctor because her brother has sickle-cell and she wants to cure sickle-cell. Like Liz doesn’t want to run for prom queen because she wants the glory and the honor of being prom queen. No, Liz wants to run for prom queen because she has to get this scholarship because going to college is the only way that she can escape her hometown and ultimately be able to help her family in any real way,” she explains. “So when you think about it through that lens, you think about like the interworkings of a character like Liz Lighty, Liz is always going to be more concerned about the people around her than she is of herself,” and as such, that means she would turn to forgiveness whenever she can. Sometimes, her forgiveness comes out of understanding and sometimes out of not being able to hold that grudge any longer. Something Leah and Liz have in common.

When it comes to creating dynamics in the book, Liz’s relationship with her little brother Robbie came the easiest because it resembles the close relationship Leah has with her little sister. In terms of the most difficult, Leah chooses Gabi and Liz. “Gabi and Liz are a little more complicated to write because it’s difficult to capture on the page like the nuances of loving somebody and finding flaws in them,” she says about their friendship. “Like Liz knows that Gabi is messing up, she can recognize pretty early on like, ‘Mmm, I don’t feel entirely comfortable with the ways in which Gabi is trying to spin this campaign into something that I’m not.’ But also, Liz has such a deep sense of loyalty to Gabi because Gabi was the only friend she had when her mom died.”

Even as their relationship grows rocky, it’s all the moments when the two were there for each other that keeps Liz from giving up Gabi and not wanting to give up on her intentions despite the orchestration not being the best. “It’s hard to do that in a way that’s satisfying I think for readers who maybe have not felt that way about somebody before. So yeah, that relationship was complicated,” she admits. Part of that also comes from the fact that the manuscript had to go through edits which resulted in parts of the story, such as a lot of Gaby’s backstory and home life being cut out. “When you can’t include all those things, it’s like, how do you reframe this relationship so it’s like I don’t have to say it in order for you to kinda get it and that was difficult.”

Going from 90,000 to 73,000 words means the book had a lot left on the cutting room floor, but Leah assures that the heart of the book was always the same. “It was always circling back around to the ideas of family and found family, queer Black joy, radical love, and reciprocity. Those all remained the same.” One difference that she shares is that early on Jordan was queer too and was originally a twist at the end, but Leah found it more interesting to explore the ways in which on a surface level, he could come across as a stereotypical all-American jock with a personality and existence where below the surface he’s actually isolated in the community he resides. “Also, I’m tired of queer readers getting got at the end of the book like, ‘Haha he was a jerk because he was gay all along!’ Like come on we gotta move past that,” she adds.

We talk about the ways in which queer narratives in young adult media needs to veer away from centering stories where queer youth (especially Black queer youth) have to experience trauma and harm in their relationships/from their love interests before they can experience the love. “Liz gets outed in this book and it’s actually really tough for some readers to stomach which I understand,” Leah admits. “But, I also wanted a love that was like largely free from trauma. Like Liz’s trauma is not stemming from her relationship with Mack–the stuff that’s going on would happen with or without Mack being there. So I just think that we have to collectively work towards queer narratives where the reward for pain is not love. Like you don’t have to suffer in order to deserve love. You deserve love just because you’re a human being,” she says reiterating the work that writers have to move away from that trope sooner rather than later.

So how did she work towards that for this book? For starters, the crafting of Liz mentioned earlier in this interview. But then, the crafting of Mack as what Leah describes to be a “wish-fulfillment” character. “I was like, ‘Okay, so if I was a 17-year-old queer, Black girl who was not openly queer and who was stuck in the suburbs somewhere, what would be the ideal girl for Liz?’ It would be somebody who reads Kimberlé Crenshaw recreationally, it likely is going to be a white person just out of proximity since there are not that many Black queer people who live out here. Not even now, I still am looking around like, ‘Aye, where y’all at?'” she quips. “But it was likely going to have to be somebody white just by the nature of the story and if it was gonna be somebody white it was gonna have to be a white girl who understood intersectionality, who was like reading Kimberlé Crenshaw just for the heck of it, somebody who got Liz’s commitment to music–like I needed somebody who was like very deeply invested in music in the same way because that was something that I wanted Liz to be seen in that way. Also, somebody whose main goal is always to look out for Liz cause I think she has a family and there’s all these people in her life who care about her deeply but I think like one thing that Liz struggles to see are people who put her needs above their own.”

She recounts an important moment in the book between the two as Liz struggles with her want to be able to have a relationship with Mack while also knowing that she needs to win prom queen to pay for college when the two don’t feel possible to coexist. “[Mack] really is interested in like being what Liz needs her to be and that’s different for Liz because Liz is used to being what other people need her to be for them,” she explains what went into making Mack and their relationship.

Along with putting that kind of thought into crafting stories, it seems like the Leah way also includes music. In You Should See Me in a Crown, her next book Rise to the Sun, and her next project all have music as an integral part of the story. “I think music plays a huge role in my life and so I think it bleeds into all the writing that I do. So when I think about music, I think about communal joy, I think about shared spaces of like triumph and liberation because that’s what it felt like for me when I started going to concerts and eventually when I started going to music festivals. Like, those are all the sensations that are tied up in seeing live music. Dave Grohl has this really good essay in The Atlantic about what it means to have lost live music in the space of this pandemic that is so, so incredible. It was so beautiful to me because it like perfectly captured all these feelings I’m having about what does it mean when we lose those spaces that for so many of us were the spaces we felt most see or most understood,” she says. “Those kinds of ideas of communal joy are everpresent in the work and so I’m always listening to music as I’m writing.”

Rise of the Sun, named after an Alabama Shakes song, takes place at a music festival over the course of four days. The title came from her admittedly listening to a lot of Alamana Shakes while drafting the book. “So the book to me feels kind of like the warm, melted summer feeling of being down south in September because that’s like the sound of that Alabama Shakes album, that’s what it sounds like to me,” she explains. In a somewhat similar vein, if you were wondering, yes You Should See Me in a Crown was named after the Billie Eilish song.

Here’s where the conversation briefly turns to us talking about the need for more Black teen angst stories. “You know who does Black teen angst like really well? Ashley Woodfolk,” Leah gives her next shoutout. “I think we need Black emo girls, we need Black goth girls, we need Black alt girls, like all these different island of misfit toys Black kids, we need them in books. I personally haven’t written any yet, don’t know when I will, but I think we run the gambit,” she says. “Anyway, the point is, music is kind of the central point from which I start any process.” The next thing she’s working on, she shares, is about show choir and the interconnectedness of music, “what it does to us, and how it brings us closer to people we thought we could never be close to.”

We talk a bit about our concert experiences (which I’m mentioning mostly so you all know her first concert was a Florence & the Machine concert at 16 which is very cool) and then a little more about craft–more specifically, about the worst writing advice she ever had to unlearn.

…Hands down the most harmful thing you can teach anybody ever, any artist ever is that their work exists in a vacuum and that it’s separate from the world that the art was created in.

The answer that she gives, she prefaces by saying that on a different day would be a different answer, but still, it’s relevant. She sets the scene for it being the first semester of her first year of grad school when a classmate brought a piece to her writing workshop about a school shooter. “I didn’t think that the piece was adequately critiquing the psyche of the shooter and I was like, it’s literally 2016, Donald Trump just got elected, and instead of talking about anything worthwhile, this piece is just trying to make us empathize with this white incel? And the writing was strong but who cares, you know? I was like, so what [that] you can string together some beautiful sentences when like the work in and of itself is harmful.”

“I was so young then, I had just started writing so I was inarticulate in that I couldn’t explain at the time why my professor’s response to this piece was so flawed but I said, ‘You know, I think you have an obligation to do some work here to like really interrogate blahblahblah…’ and my professor said, ‘Not everything has to be political.’ That is hands down the most harmful thing you can teach anybody ever, any artist ever is that their work exists in a vacuum and that it’s separate from the world that the art was created in. It does not matter whether or not you’re talking about explicit politics, politics are always going to be in the work. So even if you have decided, ‘Oh, I’m not going to talk about any of this, this is an act of privilege that is a result of politics like the body politic–however you want to think about it. There is no art that is separate from the political world,” she explains comparing it to the way that public health is an issue that links to every other issue when it comes to voting.

Thankfully, Leah is also a professor who puts as much critical thought into that work as she does her writing. “One of the most important things I think any writer, any instructor, any human who has any type of access or privilege can do is to send the elevator back down. So I make it a point in my classroom to one, it’s a learning lab, we’re all here to learn from each other. I’m not anybody’s blueprint and I don’t think that’s an effective way to hold yourself in a classroom,” she says referencing Miss Trunchbull in Matilda. “That’s the most harmful thing you can do to a student is [say] the knowledge you’re bringing to this room pails in comparison to my knowledge. Because everybody who’s coming in there is an expert in something I’m not an expert in.” She references a student last semester who wrote a Russian Doll meets Inception type story that she was amazed by. It resulted in her giving the student the space and opportunity to dissect what went into developing the work. “That was every week I was coming into the classroom and one of my students were teaching me something different,” she says in amazement and admiration. Along with establishing that foundation, she says that there’s importance in transparency as well. While You Should See Me in a Crown was in development, it looked like her students experiencing the ride alongside her and Leah bringing in her editor and connections so they could understand publishing internships.

It also looked like having honest discussions about doing the work. “I’m just not interested in hoarding knowledge. I think that it’s so counterproductive to any of the work that any of us are trying to do. Like, I do this so that I’m not the only one who gets to do it anymore. Like I want You Should See Me in a Crown to be successful because I want to sell it so that I can keep writing books because this is my livelihood, but like You Should See Me in a Crown has to sell well so that they know that this is the type of book that is marketable. I had a class full of like queer kids and I want them to know it is possible to write the book that they’re writing in spirit and in truth because this book has made space for that to happen. Just the same way that somebody else has made space for my book to exist and so on and so forth,” she explains. “I think that’s the work I’m tryna do in the classroom and that’s what I hope my students are walking away with is that one, this industry is not inaccessible and if there’s anything to tell you about how to break into it, I’ll tell you. Two: there is no one way to become a writer and I think that’s the problem with a lot of programs is everybody’s like, ‘Oh, you have to do this you have to jump through this hoop and you have to make this concession about your book and blahblahblah. No, you really don’t. I wrote a book about a poor, Black, anxious queer girl from middle-of-nowhere Indiana. Nobody told me that book was possible. Maybe it wasn’t 10 years ago, but I did it because I didn’t wait for somebody to give me permission. That’s what I hope is coming out of my classroom.”

Even as we wrap up our convo, she continues on with the hopes that she can build this classroom to extend further to more young people, to offer these resources, knowledge, and space to more low income, Black and Brown, queer students.

~~~

You can stay up to date on all things Leah Johnson by following her Twitter and Instagram accounts.

You Should See Me in a Crown is available to buy in stores and online now.