Welcome to ‘Monday Musings’!

A new segment from Teenplicity, ‘Monday Musings’ will explore personal interests and thoughts in a multitude of ways. Whether it be through lists, fan interaction, or discussion posts, each week will offer a different topic and new perspective from Teenplicity about what is on our mind. The range of topics, just like our interests, will be vast. Some might be familiar, as it could highlight previous feature stars, while others will discuss uncharted subjects for Teenplicity. They might be fun posts with a silly twist or a more serious discussion about something that could concern you.

The goal is for Teenplicity to become more engaged and involved with our readers. The Teenplicity Team is made up of fans, just like you. Let us know what you care about – a show, a film, music, an event or aspect of your life. There are no limits for what can be explored in ‘Monday Musings’ or how we present it to you.

—

We’ve done it. It’s the final week of 2019’s Black History Month. It wasn’t as joyously Black as I would have wanted it to be but Regina (BEEN) King finally won her Oscar, Spike Lee (who sometimes irks my nerves but whatever) finally won his, and Hannah Beachler and Ruth Carter became the firsts of their Production Design and Costume Design categories respectfully.

Very quick sidebar: whenever it’s announced that a Black/Brown person is being awarded the FIRST to win best something at the Oscars which has been a thing for like 91 years, I’m always torn between being like ‘AYEEEEEEE’ or being a sea of question marks. NINETY. ONE. YEARS. If I somehow make it to ninety-one years old and I’m still achieving firsts the way every award show is doing with finally realizing cis, het, white, and/or men aren’t the only people that can win these, I will be so very confused. Which I guess is fitting because I am confused whenever it’s announced that award shows are still getting firsts like this.

Okay, sidebar over. If you want to know my thoughts about this years Oscars, you can just scroll through my Twitter.

This weeks Monday Musings (edited to be a Tuesday Afternoon Musings–again, this is established on my Twitter) is about the talk of us being in a Black Renaissance, the previous Black Renaissances before now, and how these previous ones are influencing where we are now. It’s also about how I feel like we’re gonna have to learn from the previous ones to avoid a repeat of why exactly they’re looked at as moments/trends as opposed to lasting. (Spoiler Alert: it’s about audiences and profitability and the industry hyping up progressiveness and inclusivity until they decide to switch up the trend they want to sell next! But more on that later.)

If you’ve read my previous Black History Month Monday Musings, you can probably piece together that I have a deep love, appreciation, and interest in the Harlem Renaissance. It’s just a very interesting era that was so very much driven by everything that was going on at the time and yet, all of the art proves to be timeless. This is both a happy statement about how powerful the artists were and also an annoyed statement because a good amount of the art documented navigating a racist America and well……it’s timeless because we’re still doing it. Like what gives? Get it together.

So, what exactly was the Harlem Renaissance and how did it come about/what effect did it have on America as a whole? Very great question reader, thank you for asking me. The Harlem Renaissance took place during the 1920s in Harlem, New York. Although, it also kinda didn’t. A lot of influential people who participated also moved to/lived in Paris at the time. And others stayed in the midwest or the northeastern parts of America due to the Great Migration which found African American families from the south moving north in the hopes of more job opportunities and less antiblackness. As such, the Harlem Renaissance can also be referred to as the rebirth of Black Art.

At the time, it was referred to as the New Negro Movement because of Alain Locke’s 1925 anthology The New Negro. The book featured the work of many prominent Harlem Renaissance players and set out to define how African Americans were looking to change the political, social, and artistic landscape they were subject to. In other words, they were tired of all the racism and disadvantages and preconceived notions of what they could and couldn’t do. This would hopefully change that. Or at the very least, make a space for Blackness to exist and be celebrated. Ideally, it would do both.

There’s a lot of discussion on when exactly the Harlem Renaissance started and ended. Some say 1918, others say the mid-1920s is when it really kicked off. Usually, there’s an agreement that it ended around the time the decade did but that the legacy lived on forever. (The next renaissance I touch on kinda confirms and denies this.)

The Harlem Renaissance was driven by disillusionment. It carried the remnants of the Civil War and the Reconstruction Era and what it meant to adjust to life after slavery. And yet, it also carried the remnants of World War I where Black soldiers were fighting the war with the expectation that this would give Black people some kind of status and yet, they were just fighting in a war away from home while their home was still at war with their existence.

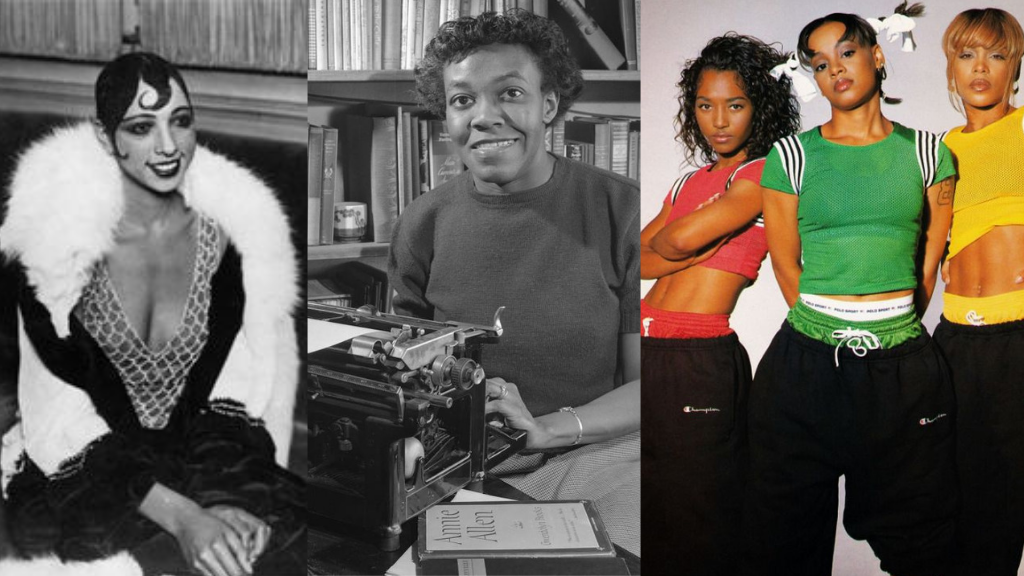

The Harlem Renaissance gave us the likes of Duke Ellington, Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, Bessie Smith, Gladys Bentley, and Dizzy Gillespie making music that flooded the streets at night in nightclubs. Josephine Baker and I cannot stress this enough, defined what elegance and carefree Black Girl Magic was. It had Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, and James Baldwin writing our stories. It gave us Shuffle Along on Broadway with an all-black creative team and cast.

There are criticisms regarding the movement and debate about the role of assimilation and creating radical Black content that sometimes sought the approval and acceptance of whiteness in a time of blackface and minstrel shows and the KKK, etc. But, there’s a quote that says how history is usually written by the “winners” and sometimes the “winners” love telling half stories that makes them look super great even when they weren’t. The Harlem Renaissance let Black people tell our own history and document it while setting up for what we could do in the future.

Now, we move on to the next renaissance, which was shortly after this one and yet, always either gets lumped in with it or doesn’t get acknowledged as a renaissance at all: the Black Chicago Renaissance. It started in the 1930s and is said to have lasted through the 1940s. It took place on the south side of Chicago (ayeeeeeee) and was mainly literary although we had some pretty dope music and visual art as well.

The Black Chicago Renaissance was influenced by the Harlem Renaissance, the Great Migration, and the Great Depression. Black folks were moving up north for more opportunities making the Black population of Chicago significantly increase and reside in a “segregated zone” on the south side (Great Migration). The Great Migration played a part establishing Chicago’s African American industrial working class. But, while Black art was being made and celebrated (Harlem Renaissance), the Great Depression hit and because of systemic racism, it impacted African Americans tenfold. Dismayed, African Americans in Chicago turned to social activism and establishing their own institutions as a way of building the Black Chicago community up since the people who were employed to help us weren’t.

There are a ton of negative notions about the south side of Chicago. A lot of them stem from racism. Actually…all of them might stem from racism–systemic and every day. When the south side became known as the home to Black Chicagoans, it became identified as the “black ghetto” or the “black belt.” And because most of the residents didn’t come from wealth or hold much wealth, the area didn’t have many resources to begin with before the Great Depression hit. Fast forward to now, the south side is still dealing with essentially being ignored and discarded because of who lives here. (While also being hyped up by many wonderful and dope artists who are following in our Black Renaissance’s footsteps–many of them, I argue, contribute greatly to our current Black Renaissance and I will hype my people up forever.)

The Chicago Black Renaissance gave us literary legends such as Gwendolyn Brooks, Lorraine Hansberry, Richard Wright, Marion Perkins, and other members of the South Side Writers Group. Their work was very Chicago based and shed light on Chicago culture, identity, and disillusionment. It also included periodicals and journals to help Black Americans find jobs and access Black art.

Our music scene put on jazz, gospel, and blues artists including Louis Armstrong. Fats Waller, and Mahalia Jackson.

Meanwhile, painters like Archibald John Motley Jr, created beautiful art that depicted Black life through such an artistic and sensual lens. A lot of what came from the Black Chicago Renaissance has also carried on to now, especially in our art and graffiti seen in Black neighborhoods (most notably Bronzeville whose name was created during this time.)

It’d be really easy to move onto the Civil Rights era next, but I want to briefly talk about an era that I think is so clearly a Black Renaissance moment and yet, it’s never been officially given the title of one although, it’s heavily acknowledged as a time of Black Excellence in art: the 90s.

In the 90s, hip hop and R&B were on equal, if not higher, footing as rock and pop music in terms of the mainstream. Black artists became trendsetters and defined what was considered cool to wear. Television lineups featured multiple shows where the casts were predominantly Black. In fact, television stations were being made with the intention of appealing to Black audiences. One example is UPN which then became The WB which is now known as The CW. Another example is, surprisingly, FOX. Meanwhile, 90s movies not only gave every white teen character at least one Black friend usually played by Gabrielle Union, but the decade also gave us a majority of movies we now consider to be Black classics.

And most importantly, all of this revolved around Black art that wasn’t just tied to the disadvantages we faced for being Black. It wasn’t just period pieces set in the times of slavery and segregation and a scene could be filled with all Black characters and they’d simply get to just exist in the comedy or the drama or the mystery or the crime as people. This era wasn’t necessarily the first time we’d seen this, but it could be argued that this was one of the first times that it seemed like respectability was never (or rarely) called into question when making Black art. Unlike the Harlem Renaissance, the work didn’t also come with a fight for acceptance–the 90s had the opportunity to just say “We’re here and what about it?”

Although, that doesn’t mean Black media in the 90s wasn’t political. It was very political. So. Very. Political. Our comedies still carried social awareness such as an episode of Fresh Prince of Bel-Air where Carlton realizes that his wealth won’t save him from facing discrimination as a Black man or racial profiling by the police. We had shows like Living Single that was groundbreaking simply because it revolved around multifaceted Black women who had different careers and defied both gender and racial norms. Lauryn Hill won five Grammy’s in one night one for a song she wrote for Aretha Franklin, one for Best New Artist, and the other three (including Album of the Year) for an album that was very much inspired by previous Black art. TLC became the best-selling American girl group (they’re only second to Spice Girls for being the best-selling girl group worldwide).

Even our children’s content centered on Blackness including Kenan & Kel which was a situational comedy set on the south side of Chicago, Cousin Skeeter where titular character was a puppet with a real live Black family and it was never questioned, The Famous Jett Jackson where the main character played a teenage secret agent on a show within a show. Brandy was such an iconic teen pop sensation, she got her own show Moesha and then changed the game when she was the first Black actress in mainstream media to play Cinderella in the best version of Cinderella to ever do it in 1997.

And I’m only scratching the surface here. There was a lot more amazing Black content in the 90s (don’t even get me started on theme songs, movies, or how we absolutely redefined what a soundtrack could do/be). However, with all of this success, it makes you wonder why, then, did it feel like such a huge and sudden switch as soon as the 2000s hit? Remember my spoiler alert earlier? That’s why. After finding much success appealing to Black audiences, the industry looked at the other audience they were predominantly appealing to at the time–white teen girls–and decided that the focus should be on them as the new trend and thus, more profitable. This change is often described as happening pretty quickly and suddenly, especially by the people who were employed at the time of it happening because most of the content was canceled and replaced with few explanations other than arguments about their ratings. (But, if you were to compare just about any current shows ratings now to just about any show that was canceled back then “because of ratings”…I mean…..ratings are just very tricky is all I’m implying.)

Still, Black artists and art held success in the 00’s, only in different ways. One of the biggest differences between the 90s and the 00’s is that the 00’s made it seem like if Blackness was going to succeed, it could only be one or two people/things at a time. (I mention this slightly in my Monday Musings post about Lemonade, ANTI, and the Grammys.) We’d have a few really popular things throughout the years that would cut into the mainstream and be celebrated, while the others fell under the mainstream radar and essentially became examples of “if you, you know.” And with the rise of social media and meme culture, our stuff started also becoming jokes and punchlines and marketing ploys without authenticity (i.e. using rap and hip hop music in things that had zero incorporation of Black folks).

So, it’d make sense why now, it’s being argued that we are in another Black Renaissance as we see multiple Black artists get their dues–most of whom are legends in the community and are only just now getting appreciated in the mainstream level. (There is SO much more room for more for the record–please tell the industry to stop patting themselves on the back so quickly.) I won’t go as much into detail about this renaissance just because we’re currently experiencing this one right now. Also, because I mainly wanted this post to hopefully show you that there is a clear link between the previous eras of Black art and now including the content that’s made and the messages.

Whenever it’s announced that a new piece of media features predominantly Black and Brown artists, trolls on social media run to saying that it’s for “political correctness” or inclusivity. Or that it’s taking away from integrity or some other lie. It’s just an attempt at discrediting and trying to place Black/Brown art as mere trends instead of holding longevity. Here’s the truth: the industry is just trends. That’s all it is. People in charge of what goes big and gets seen are mainly just looking to make things be trends and then move on because that’s how they get their money. But, as we’ve clearly seen, social media and the amount of mass creation of content has altered this in such a huge way and has given the public and the industry almost equal footing in balancing and deciding what is profitable and if it’s here for the long run. (It’s a slippery slope that’s for better or worse but then again…just about any attempt at this kind of structure might be.)

My hope is that the takeaway of the past Black Renaissances proves that our art can have longevity and that the goal is to simply just create. I think this current one has so much focus on “doing things for the culture” which is because of all of our previous influential works helped craft our culture. Especially for Black Americans who never got the opportunity to know or learn their roots beyond the ones that were planted here in America. But, a story centered on Blackness doesn’t have to be on the level of Malcolm X political for it to hold value. Coming of age stories about Black characters dealing with the trickiness of adolescence is just as valuable. Black movies and shows that are ridiculously goofy and fun are too. Same goes for Black music. And the list goes on.

As we exist in this current Black Renaissance and continue creating content later on, I hope that we’re continuing to open doors for Black stories and Black art to mean and feature a multitude of things. Just as our Black history does.

—

Did you like ‘Monday Musings’? If so, you’re in luck! Each week, Teenplicity will feature a new ‘Monday Musings’ post about things we are looking forward to, topics close to our hearts, or suggestions from readers!